A couple weeks ago I was on that week’s episode of Clockwise. I completely blanked on mentioning it here.

On that episode, I joined my friends Dan Moren and Mikah Sargent, and was lucky enough to share the proverbial stage with my friend Jean MacDonald as well.

We discussed, in 30 minutes, Apple’s possible lack of inclusion of headphones in the next iPhone, places we want to go when quarantine is over, online gaming, and watching movies with friends.

Clockwise is fun and tight; if you’ve never listened, you should.

Over 100,000 Americans have died from COVID-19, a disease that we were told will be eradicated before it’s a problem. By the man who has decided to take America out of the World Health Organization. Our neighbors and community members are protesting — and rightfully so — the deep, deep racial inequality in this country. The man in the White House told us after what happened in Charlottesville — my former hometown — that there were "very fine people on both sides”.

Black lives matter.

All lives don’t matter until Black lives do.

We are told that the United States government is classifying a group that is opposed to fascism as a terrorist organization. Our government is now… anti-… anti-fascism‽ Does that make us… pro-fascism‽

We are being told that allowing mail-in voting is dangerous by the very people who fear so deeply the results of that style of voting. Their motives are so transparent.

If this is the America you wanted in 2016 — our Black community members demanding to be treated like humans, our hospitals fighting for the lives of everyday Americans, our doctors doing their jobs without the protective equipment they need to keep themselves safe — then I don’t know what to say to you.

For me, I hope and believe we can do better. And no matter what I feel about the nominee on the blue side of the ticket, you can bet I’m going to vote like hell in November.

Because all lives don’t matter until Black lives do too.

Because Black people deserve better.

Because people of color deserve better.

Because the LGBTQIA+ community deserves better.

Because so many other marginalized communities deserve better.

Because our doctors and nurses deserve better.

Because our teachers deserve better.

Our children deserve better.

We deserve better.

I’m going to vote like hell in November. I hope you do too.

This week I joined Chris and Glenn on their Starport75 podcast again. We spent the episode discussing how, but mostly when, Walt Disney World will reopen. Naturally, I’m completely unqualified to come up with answers to such questions, but that’s never stopped me before.

At the end, we also have a bit of a “bonus round”: the boys ask me about my soda preference, and how I would spend an hour alone in Disney. I then turn the tables on them, and ask the boys which Disney restaurants are unreasonably beloved.

As with last time, I really enjoyed discussing all things Disney with Glenn and Chris; if you’re even moderately interested in Disney, you will too.

Over the last few weeks I was [briefly] featured on the last four episodes of the Stacktrace Podcast. Hosts Gui Rambo and John Sundell interviewed several independent developers, such as myself, and put together segments around common topics.

On episodes 74, 75, 76, and 77, you can hear some of my thoughts about coming up with an idea for an indie app, creating it, marketing it, and more.

Stacktrace is a podcast for nerds, by nerds, and if you’re in my line of work, I bet you’d really enjoy it.

A brand new version of Peek‑a‑View is rolling out to the various App Stores right now. There’s some big new features in this realease, so I wanted to call them out:

‼️ Custom Albums

A frequent request, many users have wanted to be able to select specific photos to show in Peek‑a‑View, rather than relying on an album that was already created. You can now do so with a “Custom Album”.

Note that this fancy new feature requires the one-time in-app purchase.

🗂 Browse by Folder

Though a very well hidden feature, it is actually possible to create an entire hierarchy of folders within Photos, and then store your albums within those folders. Previously, Peek‑a‑View would flatten your hierarchy and show you all your albums, regardless of where they live. Now, you can browse the hierarchy to find your preferred album more easily.

🐞 Bugfixes

There were also various bug fixes:

- Photos should no longer briefly appear as shrunken when swiping between them

- Improved behavior during rotation

- No longer shows previews of Live Photos in single-photo view

- Improvements to VoiceOver

- Fixed a rare crash in the Settings screen

We’re in the midst of what is easily the most challenging time of my 38 years. Everyone I know is struggling; some in big ways, some in small. Peek‑a‑View is a small app, but I genuinely hope it can provide a little joy to you and yours during this time.

To everyone that has purchased a copy, thank you! Every little bit helps.

Stay safe. Stay strong.

I’ve started dabbling with Github Actions this week. Even though I’m a team of one — when it comes to code anyway — I know myself well enough to know I shouldn’t be trusted. I decided I should set up a server of some sort to build Peek‑a‑View when I commit new code to ensure I didn’t accidentally break anything.

Tangentially, this week I also split out some code that’s shared between

Vignette and Peek‑a‑View into its own library. This new common library

that Vignette and Peek‑a‑View will share lives as a private repository on

Github. Since it’s mostly extensions and other small objects, I’m

working on getting decent unit test coverage on it. Since this

project lives on Github, like all my projects do, I thougth I’d use

a Github Action to build and test this shared project every

time I add code to it.

As it turns out, for Swift packages, this is extremely easy to do using Github actions. The default action works out of the box. To add an action:

- Go to your repo on Github on the web

- Click the

Actionstab - Click the

New Workflowbutton - Find the

Swiftworkflow and clickSet up this workflow - Customize it if required, and then click

Start committo commit this new.github/workflows/swift.ymlfile.

Easy peasy, and now I will get an email if I ever break my own build.

Github Actions

The obvious next step was to try to get Peek‑a‑View building using Github actions. Even though there aren’t any unit tests there yet, it would still be nice to have independent verification that my builds are working.

Unfortunately, thanks to the use of a couple of private Github repositories, that’s far easier said than done. I found some really hacky ways of doing it — in short, using a Github Personal access token — but that would require me to expose what is effectively a password in my own repo. Yes, a private repo, but still; that path seems undesireable.

That got me to thinking: what if i didn’t rely on Github for this? Especially since running builds on Github’s servers is not free if you do too many of them. If only there was a way to do these builds locally, so they’re free, and I can take some more shortcuts with regard to authentication.

Xcode Bots

Introduced in 2013, Xcode added a new feature: Bots. Xcode Bots are basically ways of performing continuous integration locally, on a server of your own control. Thankfully, I have a Mac mini for exactly these sorts of reasons.

Like most Apple documentation these days, the documentation leaves a lot to be desired. As it turns out though, it’s not hard to install. On the machine you want to serve as your server:

- Open Xcode

- Open Xcode’s preferences

- Select the

Server & Botstab - Unlock using the 🔒 at the bottom-left

- Flip the switch in the upper-right and follow the prompts

Then, on the machine you use to develop:

- Open your project/workspace

Productmenu →Create Bot...- Follow the prompts; you should find that your server is auto-discovered using Bonjour

This worked really well and quickly for Peek‑a‑View. So far so good.

Figuring it can’t hurt to have a little redundancy in my life, I decided to try to repeat the process for my shared library. And then I immediately hit a wall.

Bots and Swift Packages

The shared library was created as a SPM package using Xcode 11. Through some

sort of magic, when I open the folder the package is in using Xcode, it seems

to create a sort of anonymous project/workspace for me to use to build and test

the package. There is no xcodeproj on the filesystem — at least, not

one that I’ve seen.

So I opened up this phantom project, and tried to add a Bot for it the same way that I did for Peek‑a‑View. When the Bot attempted to build it, I kept getting errors about how it couldn’t find a project or workspace.

After some fumbling about, it occurred to me that there isn’t a project nor workspace checked into Github, and the first thing the Bot does is pull down the source from Github. Annoying as it was, the error was correct: there wasn’t a project nor workspace. Unfortunately, the Bot isn’t capable of the same magic incantation Xcode is for Swift Packages; it needs a file on the filesystem to load.

Hm.

SPM packages don’t generally have projects/workspaces, so I wasn’t sure what

to do. Then I had an apostrophy epiphany.

On the command line, I could have SPM create a project for me. When I am in the root of my package:

swift package generate-xcodeproj

This drops a file on the file system. My shared library is called Macma and

thus the above will drop Macma.xcodeproj right where I’d expect it.

I then closed the copy of the phantom Macma project, and opened the one

that I just created. Using this project — the one created by the

swift package command — I created a Bot. That was an improvement,

but I wasn’t out of the woods yet.

The good news is that the Bot knew which project to look for, but the bad news is that it still isn’t there, because it’s not checked into Github. Now what?

Easy mode would be to just check in that new Magma.xcodeproj file into Github,

but that felt redundant and wasteful. Perhaps there was another approach?

Bot Triggers

I quickly realized that I needed to have the Bot generate its own Macma.xcodeproj

every time it did a run (an Integration in Bot parlance). That’s easy enough: I

just needed to add a trigger.

Back in Xcode, in the Macma.xcodeproj project, I edited my bot. The final tab

in that dialog is Triggers. There, I added a new Pre-Intergration Script, which

I called Prepare Project. The contents of that trigger are as follows:

#!/bin/sh

cd ./Macma

swift package generate-xcodeproj --enable-code-coverage

Now, every time the trigger is run, before the build/test process begins, Swift

Package Manager will re-create the xcodeproj dynamically. By the time the

build/test starts, it’s there and waiting.

I certainly could check this into Github and make things easier, but I rather like having it dynamically created every time, ensuring the repo remains “pure”.

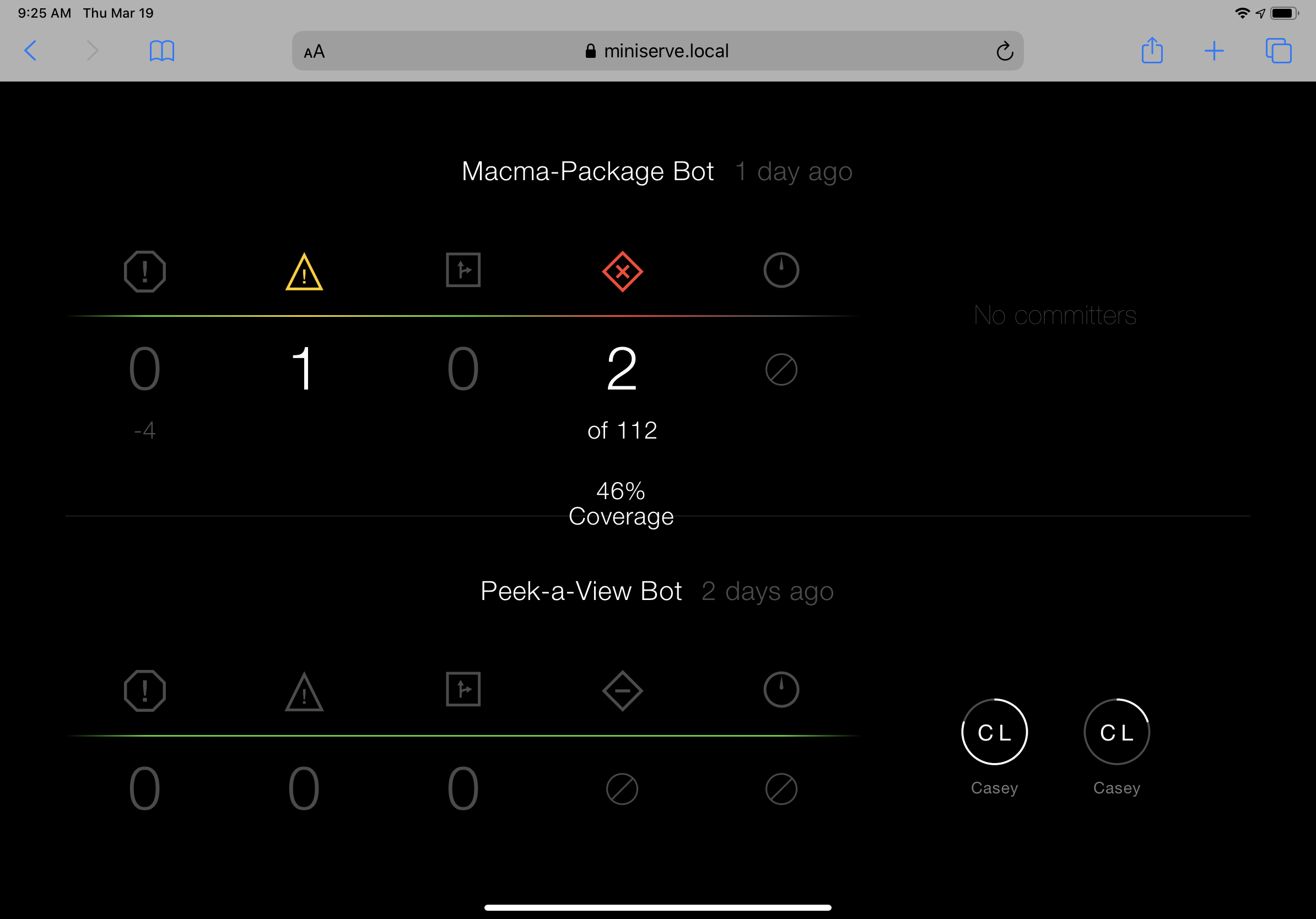

Now I have Xcode bots running for both Peek‑a‑View and Macma. If I want to, I could even set up an iPad with this snazzy Xcode Bots status page:

In a perfect world, I’d prefer to have a Github action for this, to further independently verify all is kosher, but I’m really pleased to have this new tool in my [local] arsenal.

Today I joined Zac Hall of 9to5Mac on his Watch Time podcast. On this episode, we discussed, well, a whole bunch, actually; primarily my use of my Apple Watch while I exercise. I’ve become a semi-regular casual runner, and I love running with just my Apple Watch and AirPods.

We also discuss a few other things, including, surprisingly, the right way to wash a car.

This was a really fun one to do; I love when I can have a meandering conversation like this and feel like it had a good flow to it.

As far as I’m concerned, it’s impossible to spend too much time talking about

Disney World. You may not agree, and you’re wrong that’s okay.

This week, I joined the Average Dis Nerd on his eponymously named podcast. (His podcast is kinda sorta The Talk Show, but with a Disney/Universal theme). On this episode, we discussed a variety of topics, including Disney+, technology at Disney parks, Disney’s iOS offerings for parkgoers, cameras at Disney World, and more.

I had a blast on this one; I hope you like it too.

Curiously, it all started with a trip to Disney World.

We went for my son’s fifth birthday. He hadn’t been to Disney since he was barely more than an infant. Our daughter, Mikaela, had never been.

Ever-so-independent, even just shy of two years old, Mikaela had strong

opinions about everything when she was willing to ride in the stroller.

After a few days at Disney, my wife and I discovered what would calm

her down: browsing the Photos app on our phones, looking at the pictures

we had taken on the trip so far.

This was utterly terrifying.

Photos isn’t really designed for this, and makes it possible — if not easy — to delete or edit photos. Given that these were the only copies of photos we had taken on the trip, I was scared that Mikaela would accidentally delete one or more of them.

Once we got home from our trip, I knew which app I wanted to write.

Peek-a-View

Peek-a-View is, at its core, a read-only photo browser.

It is designed to be safe to hand to anyone, and know that you’re not going to need to worry about the safety of your photos.

When paired with Guided Access — the Apple tool that lets you lock your phone into one app — it is the perfect Mikaela-safe photo browser.

Peek-a-View can be used for other reasons though. Perhaps you’re showing off a series of screenshots to a client. Perhaps you want to share your vacation pictures with a friend, but only your vacation pictures. Peek-a-View also lets you select a particular album to view, thus limiting inquisitive eyes to only the photos you know are safe.

Purchase

Peek-a-View, like Vignette, has a free tier, with a one-time $5 purchase to unlock more functionality.

Peek-a-View is limited to showing only the 20 most recent media items for free; the unlocked version has no such limit. Furthermore, if you do unlock Peek-a-View, you also get a series of fun alternative icons you can choose from.

Business Casual |

Eco Friendly |

Flat and Friendly |

High Contrast |

Trendy |

Thanks

I owe a great debt of gratitude to my friends Jelly and Ste. Jelly (of GIFWrapped fame) gave me a ton of technical help, and some design pointers as well. Ste (more at his website) did the app icon, store screenshots, as well as providing many suggestions for Peek‑a‑View’s design.

I’d be honored if you gave Peek-a-View a try, and even more so, if you decided to throw a few bucks my way for making it.

This week I joined Jonathan Ruiz and Mark Fransen on their tech show, Everyday Robots. On this episode, we discussed my history as a developer, my journey into being an iOS developer, and finally my transition into being an indie.

Though Analog(ue) is probably the canonical podcast series about my history and journey of the last few years, this episode of Everyday Robots is a really terrific summary. If you want a ~75 minute answer to “who the hell is Casey?”, this episode is it.